Cameroon has enjoyed a relatively stable political environment since it gained independence in 1960 when former French Cameroon and part of British Cameroon merged and thereby became Cameroon we know today. The country measures 475,440 square kilometers and it makes it the 25th largest country in the continent by area. Its population of about 25.2 million makes Cameroon the 16th most populous nation in Africa. French and English are the two official languages, with approximately 250 other languages.

Cameroon is the largest economy in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), a region confronted with several challenges because of persistent insecurity, especially in Cameroon, Central African Republic, and Chad, as well as the lingering effect of lower oil prices experienced during the end of commodity super patterns. Along with other CEMAC countries, Cameroon put in place fiscal adjustment measures aimed at mitigating the potential impact of terms of trade shocks, to restore macroeconomic stability and confidence in the common currency area. Nonetheless, the economic and financial environment has remained fragile in the region. Despite the challenges, real GDP growth in Cameroon rebounded growing by an estimated 4 percent.

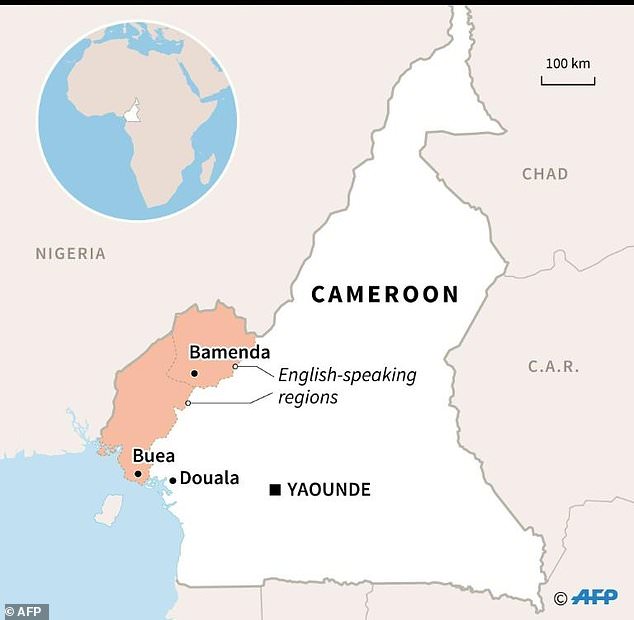

The increase was driven mainly by domestic demand (consumption and investment), an increase in natural gas production (with a new liquefied natural gas offshore terminal coming on stream), and an uptick in agriculture, boosted by stronger demand from neighbouring Chad, Central African Republic, and Nigeria. Although Cameroon's economy remains resilient, its exposure to fluctuations in commodity prices, a protracted armed conflict in its north involving the terrorist organization Boko Haram, and an armed conflict in its English-speaking regions, pose significant risks. Ongoing efforts to develop the agro-pastoral and fisheries sectors and to provide support for private sector development could mitigate these risks and further diversify the sources of growth to strengthen the country's economic resilience and improve its competitiveness.

.

Politically, Cameroon has one of the longest-serving rulers in Africa. Paul Biya has secured military loyalty: counterbalancing rival forces, personalizing command hierarchies, ethnically stacking both the regular military and presidential guard, and providing extensive patronage benefits to soldiers.

The president's centralization of power means that he can manipulate institutions to position supporters and punish detractors. There is no apparent institutional mechanism within the ruling party for choosing a successor. A succession crisis is likely at some point in the future.

The last presidential elections which saw the victory of Mr. Paul Biya were held in October 2018. The next general election is scheduled for 2025.

Security issues:

The Northwest and Southwest have seen an increase in violence since 2017, with armed groups staging multiple attacks, including raids on security forces and mass kidnappings. Cameroon's Far North region also remains vulnerable to sporadic cross-border attacks from Islamist groups in the Lake Chad Basin.

Crime is prevalent in urban centres, with foreign travellers most likely to be targeted in incidents of petty and opportunistic theft. Civil unrest occurs intermittently, with high unemployment and living costs remaining the most potent triggers for outbreaks of disturbances.

Cameroon has been experiencing an interplay of protracted crises that continue to define political, economic, and social developments in the country.

Long-standing grievances in the Anglophone community in Northwest and Southwest regions, following decades of the marginalisation of the minority English-speaking regions by the Francophone-dominated Government, escalated into widespread protests and strikes in late 2016. This has resulted in the emergence of different separatist groups clamouring for the creation of a self-proclaimed Ambazonian Republic in the Northwest and Southwest. Clashes between the military and separatist forces have intensified insecurity in the regions, leaving over 626,000 people internally displaced and about 87,000 seeking refuge in neighbouring Nigeria as of February 2023.

Verdict:

Mr Paul Biya assumed office as president on 6 November 1982, after seven years as the country’s prime minister, becoming only the second head of state since Cameroon’s independence from France in 1960. However, given that Mr. Paul Biya has weak popular support and is presiding over a disintegrating state, it is unlikely that Cameroonians will wait idly until the next election. If protests in recent times are any indication, Cameroonians more especially the youth have demonstrated their dissatisfaction with political leadership and their willingness to risk their security to raise the visibility of the challenges in the country. The scars of colonization are very much also at the forefront of the Anglophone and Francophone divide in the country and create the opportunity for terrorism to flourish.

Nonetheless, if these challenges are adequately addressed, Cameroon could become one of the economic powerhouses in Africa. Risk is relatively high.