When a huge gas find was made offshore in Mozambique years ago, the country was sure to benefit from it like many countries across the world have. Having fought a long civil war that was influenced by Cold War politics, the find was expected to change the fortunes of the country in unprecedented ways. The long period of the war had made it poor.

The country was one of the four territories Portugal gained in the partition of Africa in the latter part of the 19th century. It took years of rebellion and a coup d’état in Lisbon before Mozambique and other Portuguese colonies were granted independence in 1975. Almost immediately, a civil war between the different factions broke out. This was exacerbated by the Cold War politics in Africa.

Mozambique only witnessed relative stability when the Cold War ended in the late 1980s and early and early 1990s. The discovery of the huge deposit of hydrocarbons was therefore relieving for the economy that has had multiple decades of lost years.

Not long after the find, the country had investors putting in a whopping $20 billion into the development of the gas. This was unprecedented in the investment history of the continent. TotalEnergies alone invested almost $4 billion. The French company had bet on the success of the project and prioritized it in the continent. Other investors equally had high hopes in investing in a lucrative project on the Indian Ocean coast of Africa.

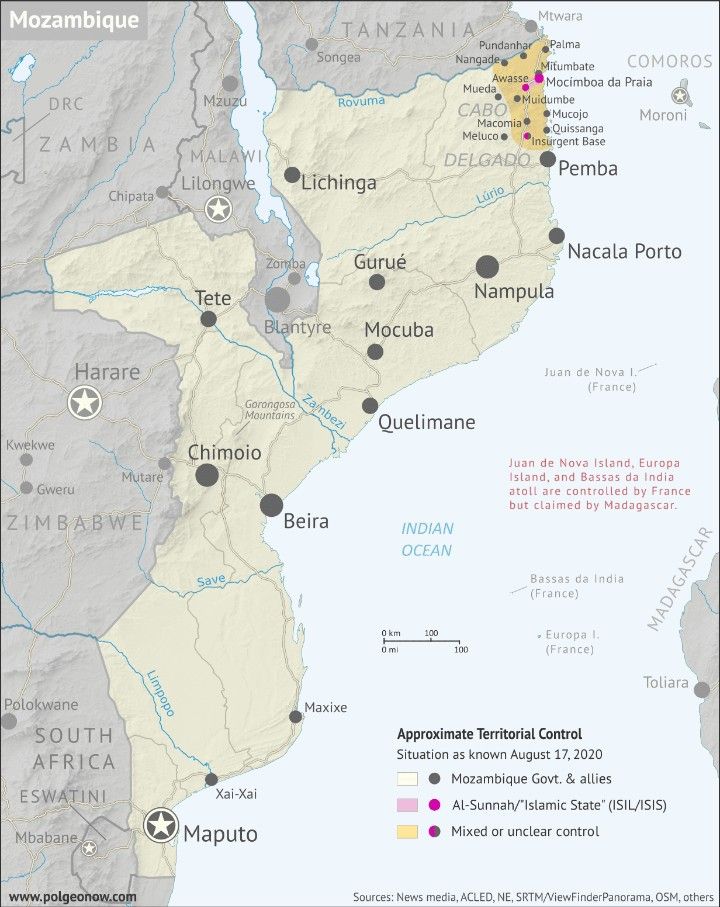

While the potential boom had attracted money and global interest, militants and violent extremists also saw the opportunity to assert their presence in the country’s North East—where the hub of its infant petroleum industry is based.

In a jihadi rebellion, ISIS-affiliated Ansar al-Sunna (also loosely called Al-Shabaab in Mozambique) has launched a series of indiscriminate and brutal attacks in communities around the region. This disrupted the project with ToatalEnergies suspending its operations.

Admittedly, global terrorism is finding a foothold across Africa. In North Africa Libya, Tunisia and the North Sinai of Egypt have al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates posing a threat to state security and stability. West Africa is the most affected region by violent extremism in the continent. The Sahel states of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have been mostly affected by the activities of jihadists. Currently, these are facing political instability not seen in many years

In the Horn of Africa, Al-Shabaab has over the decades terrorized locals and governments with incessant attacks. While the government has in recent times gone on the offensive against the extremists, the presence of ISIS affiliates in the country has complicated insecurity the country. Interestingly, extremists have also further found a foothold in the forest regions of Central Africa. ISIS, Central African Province, ISCAP is currently operating in Eastern DR Congo, from where it occasionally attacks Western Uganda.

This notwithstanding, in the Cabo Delgado region of Mozambique the ISIS affiliate present has been a homegrown movement that has been enabled by socio-economic challenges. Granted, in many places of Africa where jihadism is thriving there have been socio-economic reasons that have contributed to the situation. In Mozambique, this has been relatively more acute, as the civil war and inimical colonial policies adversely affected its development.

Years of over-concentration of the scanty development in Maputo—the capital down south—and its immediate regions has meant that the north was largely neglected. This entrenched endemic poverty and poor social infrastructure in the region in the north and other regions.

Just like other places in Africa, where the neglected locals residing in resource-rich regions have rebelled against local and central governments, the situation in Mozambique has been capitalized on by extremists to destabilize the region and disrupt investment. In the southeast of Nigeria, specifically the Niger Delta, militants, albeit not jihadists have for years intermittently disrupted and sabotaged the petroleum industry of the country. Youth in the region have lamented the development gap between the region and other regions of the country. Unemployment, poor infrastructure and the lack of it have also been major factors threatening to destabilize resource-rich areas across Africa. Extremists are not oblivious to these and are willing to “utilize” the indignation that follows.

Despite what seems to be an insurmountable problem, investors and governments can do a lot to reverse the situation that has become a major characteristic of Africa’s resource curse.

One important means by which the debacle could be reversed would be to develop a business model that invests in the social welfare of host regions of projects as a condition precedent to undertaking major projects like that in Cabo Delgado. Investors and governments should not wait for the projects to be completed before helping the communities that host them. This should be at the core of the investment proper. When people who have been denied critical infrastructure over the decades suddenly see the building of facilities and other infrastructure to extract one resource or the other, they often feel exploited and hence become resentful toward central authority and by extension investors. For this reason, the building of infrastructure like schools, hospitals, and roads among others should be part of investment packages.

This idea is as important as how it is carried in the various localities. The implementation of infrastructural projects should not be left to the sole control of governments. Mostly, resources are diverted to other areas that serve parochial interests. To avoid this, the execution of the social projects could be under the management of consortiums jointly appointed by governments and investors and granted some level of autonomy in the execution of their functions.

With this, vital services like education, health and transport among others could be effectively delivered. These could help counter the actions of rogue local actors who seek to derail investments. Extremists who seek to exploit development gaps and deficiencies to court the sympathy and active support from local communities where resources are found will find it difficult to achieve their goals. Yes, when people see the benefit of resource extraction impacting their lives, they rarely disrupt it.

Furthermore, employment for local youth could be more pronounced after the completion of these social projects and the main projects investors seek to undertake. Social infrastructure like schools and hospitals would need significant human resources to run. Here too, the focus on available human resources in the local areas where multinationals operate as well as the training of more locals to fit the jobs required in the various sectors must be prioritized. Also, on completion of projects and the commencement of operations, a significant quota for job allocation should be given to locals. The training of locals to qualify for medium and higher management positions within guest firms should be encouraged. Scholarships could help in this direction.

While some firms and investors in Africa have already made efforts in this direction, the initiatives are often not comprehensive. The complex nature of African societies requires that any such programmes are well thought out and implemented with guidelines. In south-eastern Nigeria and elsewhere the refusal to invest in the people and their communities in the early stages has cost investors more than they had expected—if they ever did. Recent moves to correct the failure have been arduous.

With the rising incidence of violent extremism and militancy, it has become imperative for investors to—right from the start—demand that proactive measures are put in place to address socio-economic challenges before they start their operations. Insurgents are aware of gaps and are exploiting them unflinchingly.

While this could be challenged by governments and bureaucracies that benefit from the status quo, collective efforts by investors and the backing of regional and international organisations could make it work. In recent times Rwandan and South African forces have helped bring relative stability in the Cabo Delgado region. Regardless, the insurgency is not completely over. Refusing to address the challenges could, therefore, be costly.